Bodies, Bodies, Bodies

What does it mean to live in your body? I try and answer that with the help of Jasprit Bumrah, women runners, and of course, Shanta Gokhale.

“Can I just skip this?”

In the litany of things that would elicit this reaction, playing any kind of sport is probably at the top. Sports and I have never got along. I was the kid reading in the corner during games period, a selective love for cycling and badminton kept me going through my teens, and as an adult when I select “Sometimes” on Hinge to the “exercise” question, I am frankly exaggerating.

But I have had to change. As age and stress hits, you realise that the wisdom of “move your body, and your mind will thank you” is true. So occasionally, I sign up to play a sport, any sport, to shake off the inertia of a life of reading and writing. This weekend, it happened to be a game of pickle ball. On a Saturday. In the morning. And so the inevitable question of, “can I just skip this?”

The good news is, that I didn’t skip. The even better news is, I had a fun time. (An aside: We need more sports that are no rules, just vibes.) But the clarity I felt in the aftermath of that morning got me thinking closely about bodies — not just as physical carriers of organs that keep us alive, but as a being all on its own. What does it mean to fully live in our bodies?

One kind of people who might be able to answer this question are athletes. I have been following the Border-Gavaskar trophy, and specifically the exploits of Jasprit Bumrah with fascination. (Yes, I am as surprised by this sentence as you.) In the first Test against Australia at Perth, Bumrah was largely considered to be “unplayable.” Reading about the match, these few lines by Barney Ronay about Bumrah’s bowling struck me,

“First because Australia’s top order looked utterly spooked, unable to read any of the lines, angles or movement. But mainly because it was basically a piece of art….This is the mark of Bumrah’s brilliance. When he’s good it feels like step change, a reinvention of the thing you thought you knew, cricketing cubism.”

What does it mean to have so much control over your body — over the tiniest degrees in the way you perform an action — for it to become a work of art? If you have played a sport since you were a scrawny kid, like this profile of Bumrah by Sharda Ugra describes beautifully, how does your relationship with your body change? Do you look at it like a tool that allows you to do your job well? Or do you start looking at it with awe and worry — because your body is the thing that allows you to feel a touch of greatness? When Micheal Phelps — the peak of what a human body can do, surely — talks about post-Olympic depression and suicidal ideation, is he talking about the limits of the body? Or, the mind?

I realise that the above paragraph has more questions than answers. And that’s because, surprise surprise, I am not an elite athlete who has even the slightest idea what it means to devote a lifetime to strengthening your body. So then, I start looking for answers elsewhere.

In the stories of bodies that read and write.

Back in the lockdown, when everyone was taking up some hobby as a way to swat away end-of-the-world doomsday, I decided to take up running. Had I run before? No. Did I think I could? No. Did it become the only workout I have stuck to for a period of time? Yes. During that time, I started looking for things people had written about running and came across this piece by Bella Mackie. Mackie, a writer, discovered running at a time when her first marriage exploded, her severe anxiety meant she was close to a breakdown, and she couldn’t stop crying. She ran on a whim. And discovered she hadn’t cried on that one jog. And so, she decided to….keep running. She writes,

“When you run, your body takes your brain along for the ride. Your mind is no longer in the driving seat. You’re concentrating on the burn in your legs, the swing of your arms. You notice your heartbeat, the sweat dripping into your ears, the way your torso twists as you stride. Once you’re in a rhythm, you start to notice obstacles in your way, or people to avoid…My mind, accustomed to frightening me with endless “what if” thoughts, or happy to torment me with repeated flashbacks to my worst experiences, simply could not compete with the need to concentrate while moving fast. I’d tricked it, or exhausted it, or just given it something new to deal with.”

I have bookmarked this paragraph because, this, indeed, is how running feels like for me. I don’t enjoy it by any means. But the rhythm of running and the excitement of using my body to move forward, to propel ahead, means that for some time I can live in my body and not my mind.2

The body then, becomes the anchor, through which the mind can live a life that it wants.

In her memoir, “One Foot on The Ground,” Shanta Gokhale uses the body to tell the story of her life.3 She takes body parts — heart, teeth, skin — and maps on to them her life events — first love, marriage, babies. Writing about using her body as the centre of her memoir, Gokhale says,

“I was being told to look at the body organ by organ, accepting it for what it was. The end to which this was meant to lead was not the end I was interested in. I did not want to contemplate the body in order to detach myself from it. I would never want to do that. I loved my body too much for what it had given me and for what it had not. However, the idea of looking at the body and its life not as incidental to mine but central to it, excited me.”

Reading this for the first time brought home how wrong I was to think that the mind could exist independently of the body. Actually, I must admit, more arrogant than wrong. Even for my ambitions as writer, the body is essential. In fact, like Gokhale demonstrates in her excellent memoir, in the hands of a prodigious writer, the body can become the tool with which to write. The pen. And, the canvas.

So then, is the body an ever-changing, amorphous thing? If bodies exist to decay inevitably — if I remember correctly the entropy lessons from school — do we not expose our bodies to the world? As I write this, Bryan Johnson — yes, the billionaire who doesn’t want to die — is making his first India trip. His entire shtick, to put it mildly, is immortality. He wants to live forever; to fight against the entropy that makes death the ultimate fate for everyone. Like a TIME profile on Johnson describes,

“…he’s spent more than $4 million developing a life-extension system called Blueprint, in which he outsources every decision involving his body to a team of doctors, who use data to develop a strict health regimen to reduce what Johnson calls his “biological age.” That system includes downing 111 pills every day, wearing a baseball cap that shoots red light into his scalp, collecting his own stool samples, and sleeping with a tiny jet pack attached to his penis to monitor his nighttime erections. Johnson thinks of any act that accelerates aging—like eating a cookie, or getting less than eight hours of sleep—as an “act of violence.”

The body must be respected for all that it does. But even the most elite of the athletes would agree, that surely it can’t be preserved like a museum artefact. We all aspire for our bodies to be well-oiled machines. But, machines don’t become vulnerable. They can’t fall. They can’t feel — like I felt yesterday after a sweaty and tiring game— an intense desire for butter masala dosa. But I couldn’t help but wonder, am I losing the gains I made while playing for an hour and a half. Did my body deserve better?

But here’s the thing — my body deserves the life it wants to lead. I don’t want to live forever, thank you very much. I don’t want — and definitely can’t by any stretch of imagination — be Jasprit Bumhah. I want to be active and healthy. I want to play a sport occasionally, dance every weekend, and avoid major health issues as much as I possibly can.

But also because we are human beings that can live between extremes and have bodies that function with the purpose of making us feel gloriously alive —I want to eat one butter masala dosa.

Extra crispy, if possible, With nimbu pani — sweet and salty.

Thank you as always for reading. I would love to hear from you, so hit “Reply” to say hi. If you liked what you read, share it with your cricket-fan friend. If you didn’t like it, share it with your exercise-nerd friend.

I’ll write again, soon.

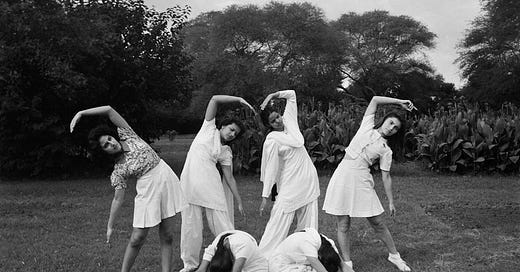

Photo Courtesy: Keep Fit’ Class at Lady Irwin College. (New Delhi, 1945-46.) by the great Homai Vyarawalla)

The need for writers to find a refuge in their body is an old one. Just ask Murakami, who has written a book on running, and how the discipline of running taught him to be a better writer. But it is a pleasure that is gendered.

A memoir that I am pretty sure I have recommended in every edition of this newsletter. Almost.

Really enjoyed this piece and the many threads it pulls at. Not to be rude, but Mr. Johnson is deep in Bizzaro territory.