How Lonely Are You?

Thoughts on loneliness via Quora, and Amrita Pritam. Plus, best links of the week.

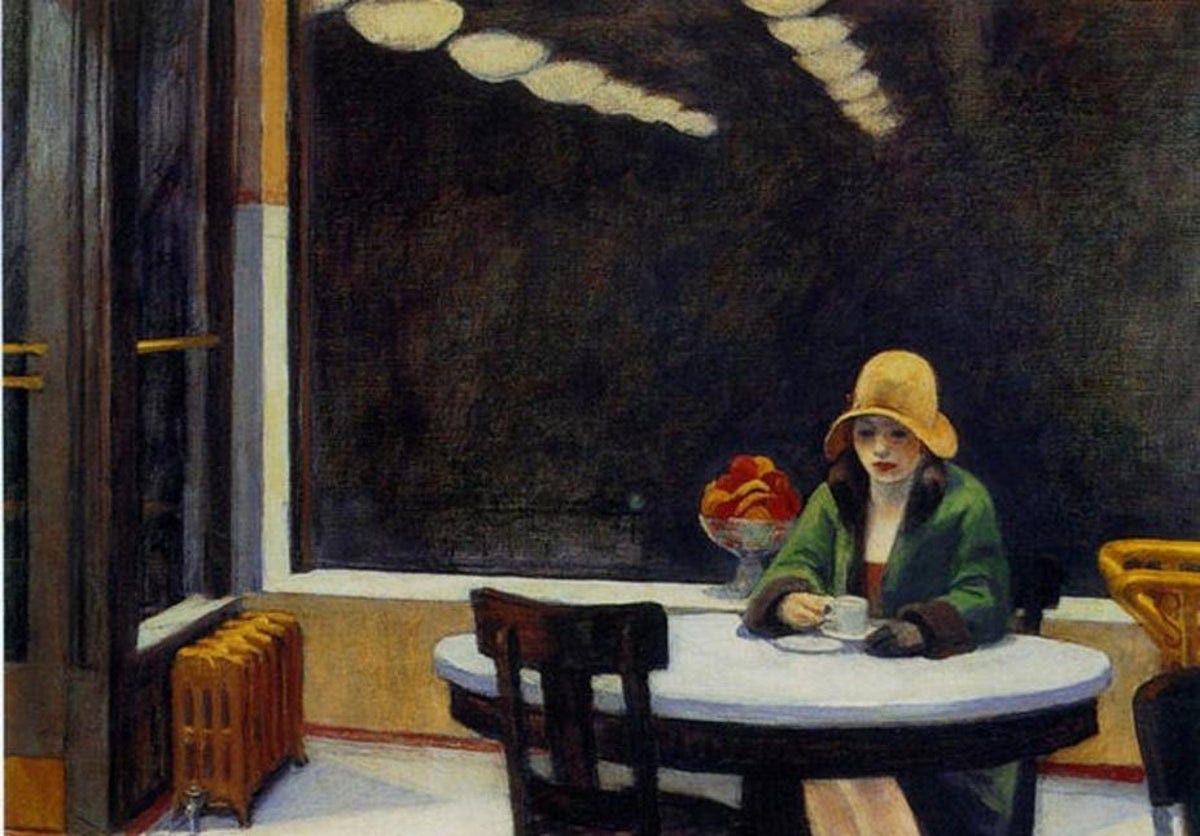

‘Automat’ (1927) by Edward Hopper

“I make a Whatsapp group where I add my mom’s number and chat with myself.”

What does loneliness feel like? The answer to that question differs for us all. For some, it’s an indescribable feeling that suffocates. For some, it’s an easy equivalence to being alone. And for a lucky few, it’s an abstract concept. This sentence was how one person on Quora chose to define a feeling that eventually comes for us all – loneliness via a Whatsapp group. An echo chamber of one.

Of course, I came upon this answer also via loneliness. A brand of loneliness that has become so widespread that there is now a name for this phenomenon – revenge bedtime procrastination. Defined first in a tweet by journalist Daphne K Lee, it’s basically a name for all the hours you spend in bed not sleeping and scrolling through Instagram – or whatever is the poison of your choice. It’s been argued that revenge bedtime procrastination is a psychological response to long working hours, and how we feel the need to “steal back our time.” But if you view those stolen hours from the other side of the lens, it’s also is the time when you are postponing being a part of the world. An imposed loneliness, then.

It was during one such scrolling-sessions that I found the question “How lonely are you?” on Quora. Through thousands of answers describing this one question, one thing struck me. How loneliness was defined within the framework of technology – that very thing that was supposed to bring us closer.

“Netflix is my only friend.”

“Friends are just contact numbers on my phone.”

If the human civilization’s answer to “how lonely are you” is reflective of the generation we belong to, then surely, loneliness in the twenty-first century is intertwined with technology.

We pick up our phones to feel less lonely. Only to find ourselves lonelier than we ever thought we were.

I know, I know. That technology makes us lonely is not a new argument. In fact, I think I distinctly remember arguing this very point in seventh standard in a school debate. But what I have been thinking over, and find fascinating, is how technology – and the world it opens up has given us context to understand our lives in which we feel even lonelier than before. Possibly, the loneliest we have ever been.

Let me explain. I have been reading a book of letters between Amrita Pritam and Imroz. A series of letters written by Amrita Pritam describe a trip to Russia in the early 1960s where she was invited as a guest. She writes in her letters of the alienation – and thrall – of finding oneself in a new city. While describing how she is enjoying being in a new country, she also writes of akelapan, of “feeling alone.” She writes how she has now decided that “at her age” it’s no longer desirable for her to travel to new countries alone; she would rather have her “jeeti” with her. (“Jeeti” is how she used to address Imroz.)

Reading those letters in 2022, frankly, feels like a revelation. Because despite the inconvenience of letters being the only way to keep in touch with someone you love, what comes through in Pritam’s letters is not loneliness. But the certainty of being deeply loved by someone even when you’re separated from them by thousands of kilometers. She is feeling alone, and yet it seems to me, she is not lonely. Contrast this with the sinking loneliness that one feels, when in 2022, despite Whatsapp and video calls, an unread message makes us feel despondent. It’s as if what we’re looking for, when toggling between DMs on many social media platforms, is certainty.

Of connection. And of feeling like we’re loved. Like we’re needed.

Maybe if your world is smaller, it is possible to feel more at home in it. So, loneliness, then, becomes something that doesn’t have anything to do with being alone – physically or otherwise. It’s not an empty WA chat box. Or, a silent phone on a birthday.

Loneliness – like all things in the world – is about context.

Are you at ease within the context you find yourself in, within the world? If yes, then that certainty nullifies any feeling of alienation that may pop up. Irrespective of whether you live in 1962 or 2022.

But if the expanding context of the world troubles you, if seeing all your friends in cosy house parties on Instagram makes your room feel smaller for example, then what you’re grappling with is not loneliness via technology. It’s the age-old struggle of finding your place in the world.

And so, here’s my half-baked thesis: With loneliness, maybe the solution, funnily enough, lies within.

Within the honest answer to one question — how lonely are you?

(As is evident from this newsletter, I am still trying to puzzle out what loneliness means. This is not a treatise by any means. I am not even sure this has the coherency of an essay, actually. This is just me thinking through some thoughts, and using this newsletter as a way of putting them out in the world. So, if you have any thoughts on loneliness, or otherwise, please feel free to reply to me!)

LINKS OF THE WEEK:

I have avoided reading Hanya Yanagihara for vague reasons to do with feeling wary of how she writes of trauma. Parul Sehgal in The New Yorker articulates some of that discomfort, thankfully, in this fascinating essay.

"The trauma plot flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and, in turn, instructs and insists upon its moral authority. The solace of its simplicity comes at no little cost. It disregards what we know and asks that we forget it, too—forget about the pleasures of not knowing, about the unscripted dimensions of suffering, about the odd angularities of personality, and, above all, about the allure and necessity of a well-placed sea urchin.”A cure for bad days by Katie Hawkins in The Guardian that isn’t doused in toxic positivity — but in practical, empathetic advice. I sent this to all my friends as soon as I read it, because that’s just the kind of month it has been.

"And so, I vowed to live my worst life, the best that I can. What started as a silly catchphrase became a lifeline for me – a way of getting through an otherwise brutal time. Living my worst life, the best that I could, allowed me to accept my current situation while also making the most of it. Instead of wishing for a reality I couldn’t have, I embraced the shitty circumstances I was dealt.”Those who know me know that I am easily amused. It’s also where my love for ridiculous TV comes from. So, not a reading link, but I have been binge-watching episodes of CID with friends. I somehow never saw it as a kid, and so I have been loving how sincere, and fun, and camp it is! I am now so deep in the rabbit hole that I am fairly certain there’s a thesis on CID-lore coming your way, sorry.

Pick any episode on YouTube, but I started with this one on the mystery of a dilapidated house.

That’s it from me this week! I hope you’re keeping well — as well as one can anyway in These Times. If you liked this newsletter, tell a friend (or two), leave a comment, and share it ahead. If you do all three, I promise to send you more CID episodes.

I will write again next week.

Pointedly poignant. Loved the honesty in it. Thanks!

I think it's really a great point on delineating the two. Technology is just a way it seems clearer right? Like an another piece of evidence for whatever someone is going through.

I appreciate you sharing your thoughts-in-progress. I've been thinking a lot recently about what loneliness is for me, and so it's nice to see someone else also work through it.